Ōhiwa - The food basket of many hands

East of Whakatāne, in a sparsely populated segment of the Bay of Plenty, lies one of the country’s smaller and less well-known harbours: Ōhiwa. Shallow and dotted with islands, its warm waters have long been a major food resource for local iwi. For even longer, migratory birds have fattened themselves up here for their annual flight back to the northern hemisphere. As in many coastal settlements, locals worry about the impact of development and tourism on their way of life, but for now Cammy Savage can still fill her kete with cockles, and the harbour lives up to its reputation as "te raweketia a teringaringa", the food basket of many hands.

This article first appeared in New Zealand Geographic. Story and photographs by Peter James Quinn. View the original story here.

The aluminium dinghy makes slow headway against the tidal flow. Ken Barsdell, a close friend of mine and a long-time resident of Ohiwa Harbour, digs his oars into the current. Overhead, a lone gull wheels tirelessly, searching for any sign of movement beneath the surface. It must have flown over countless craft like this one, crossing harbour channels in search of kai moana.

We beach the “tinnie” on the mudflats of Motuotu Island and make our way through the mangroves taking hold along the shoreline. Ohiwa is traditionally thought of as the southernmost home of this semi-tropical tree, and while winter frosts here retard its growth, never allowing it to grow as high as in Northland, the locals have noted mangroves seeding more prolifically round the tidal fringes in recent years.

Our footprints leave a trail of ankle-deep hollows in the mud, which squelches up between bare toes and dries in crusty splatters upon our legs. Soon we reach our destination. Bending down, Barsdell points to some jagged frills poking from the mud. “Whalla!” he says, plucking a sizeable Pacific oyster from its bed. Before long our bucket is brimming.

That evening, round the embers of a barbecue, Barsdell talks about the harbour and the impression it has made on his life. Originally from the south, he arrived here by chance 23 years ago. Detouring off the tar seal in the company of a local land agent, he was shown a hillside property for sale in a quiet corner of Ohiwa, partially covered in native bush, with a neglected cottage on the flat. An instant liking for the place saw him scrape together finance and make a deposit— a hard task on a beginner teacher’s salary and over the years his initial attraction has matured into a deep love for the harbour and its surroundings.

I share his feelings about Ōhiwa. I spent my teenage years close to its shores. First there were camping holidays at adjacent Ōhope, the seaside community that connects the harbour with the larger service towns of Whakatane and beyond. Later the family moved to Whakatane, from where surfing regularly drew me to the ocean beaches of Ōhope. Eventually I started working for a local surfboard shaper who had his factory in one of the old wharf sheds at Port Ōhope.

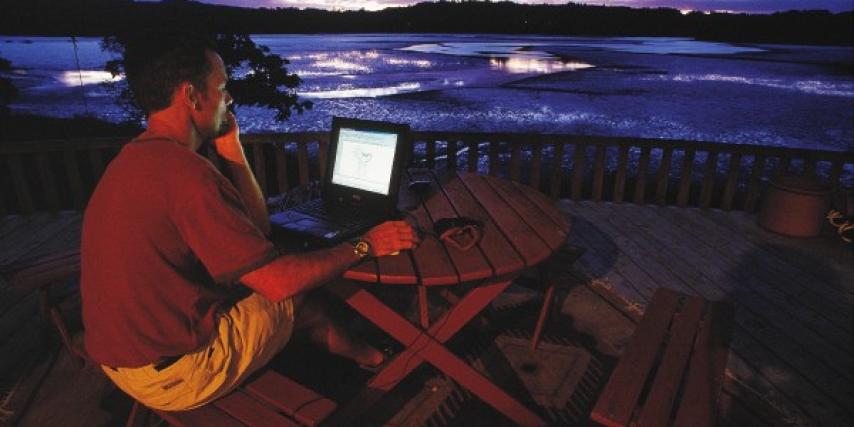

During those years spent around the port, I came to know the moods of the harbour and the way the season,, dance across its stage. How the light shimmers across the waters as the sun sinks behind jagged ridgelines on the western shore. Or the sea fog of a winter morning, thick as soup, lingers over the myriad channels and sandbars.

The talk round the barbecue becomes more impassioned. Barsdell’s neighbours, on a dairy unit, have just put the block up for auction. “That means we’ll be seeing more cars up and down our road,” he says. “More houses will be built, and land prices will sky-rocket. Everybody’s rates will go up, making it harder for us to live here.”

It’s a lament all too familiar to seaside residents. You find a place to get away from it all, and a few years later “all” comes knocking on your door. This is certainly happening in Ōhiwa. In recent years the harbour has gone from bucolic backwater to developer’s dream. Interest in land round its shores has never been greater. And as Ōhope and the subdivisions near the port become increasingly claustrophobic, the real-estate market is casting a hungry eye at what land remains round the harbour’s edges.

It was the abundance that Tangaroa, god of the sea, could deliver that drew early Maori to Ōhiwa. Over the years, several iwi have laid claim to the harbour, and many battles have been fought over who would fish its shores. Tradition has it that one such conflict in the 1840s, between local Ngāti Awa and a raiding party of Whakatohea, from Opotiki, brought Mereira, a young Ngāti Awa woman, to the brink of despair.

As the Whakatohea warriors approached the pa, Mereira, in a move reminiscent of King Solomon, held up her baby, the product of a union with a Whakatohea man, and threatened to dash it on the rocks if the men didn’t stop fighting. Sobered by this action, the two sides called off the battle and made a lasting peace pact.

These days, Upoko-rehe, a hapu of Whakatohea, are regarded as the kaitiaki, or guardians, of the harbour. One spring morning I pay a visit to Charlie Aramoana, kaumatua for Upoko-rehe, to ask him about his life here and the changes he has seen in the harbour.

Aramoana lives a kilometre or so from the harbour, at Kutarere. State Highway 2, the busy inland carriageway that links Ōpōtiki, Gisborne and the pine forests of East Cape with the paper mill at Kawerau and the port of Tauranga, flanks the settlement.

Kutarere has seen better days. Although the store still sports the trademark Coca-Cola hoardings, it’s been years since travellers quenched their thirst here. In the 1920s, however, Kutarere was a busy staging post and the harbour’s principal landing place for sea traffic, with its own wharf and a population of over a thousand. “The port of all the Urewera,” it was called.

Today there’s a scattering of weatherboard-and-Fibrolite homes, a historic green-roofed church, a marae, and not much else. The school, on a rise at the edge of the village, claims the choicest outlook over the harbour, a picturesque distraction for study-weary students.

Aramoana, softly spoken and “somewhere in his sixties,” recalls when all the general goods for the district were more often landed at Kutarere than at Ōpōtiki, with its tricky river bar. The practice continued right up to the 1960s, when a new wharf at Port Ohope, with a channel a few fathoms deeper, was commissioned. “Those were the hustle, bustle days of Kutarere,” he says. “Then the bigger boats started coming in and went up that way, and Kutarere became a backwater again.

“We used to go fishing in the harbour, and, oh gosh, those days no rods! You’d get cut hands with those old linen lines, and if you fished for half an hour, you wouldn’t be able to carry home your load of snapper. And all cocklecrunchers, too. They were big. Those were the days, man. You don’t get the snapper like that any more. Then about the ’70s the trawlers started coming in hard. We still blame the trawlers for the loss of the snapper.

“Another change we’ve noticed as local people is the rareness of the butterfish. The parore. They go around in schools, and their job, when the harbour was in its natural state, was to keep down the growth of seaweed. That’s what they lived on. But now there’s hardly any of them around.”

For Aramoana, and Upoko-rehe, the challenge now is to protect the harbour from further losses. “When I was growing up, I used to wish, gee, if only we could have a road going around here, access would be much better to get into the harbour. ‘Course, it wasn’t very long after and a road was put through, allowing people in there all the time. And you know the consequences now. More kai is going out. And all these houses going up.”

Leaving Kutarere, I backtrack past the camping ground and walk out to the sickle-shaped Ohiwa sand spit, jutting from the eastern bank at the harbour entrance. Standing there with the tide washing past, it’s easy to appreciate why early European mariners mistook the channel for a river.

Across the channel from me are the restless sands of the Ōhope spit. Without this jutting dune formation, over 2000 years old, there wouldn’t be a harbour, just a succession of coves and bays.

Sand was to be the rack and ruin of landholders on the Ōhiwa spit. Some entertained grand ideas of creating substantial settlements, only to have them carried away with the tide.

In 1873, Captain John Rushton, an enterprising Land War veteran, was granted a licence to open a pub here, on the condition that, along with pulling pints, he also ran a ferryboat for patrons to and from Ōhope. Until then there had been no official service, travellers relying instead on local Maori to ferry them across. This wasn’t without its dangers. Crossing the mouth in a leaky canoe one blustery day in 1842, two Catholic priests became worried enough in mid-channel to give each other absolution.

With the Ferry Hotel established, a small township soon rose beside it, and sections were offered for sale. Taking little heed of the proverbial adage that advises the best foundations to build on, settlers quickly erected homes on the spit. A post office was opened in 1877, and the harbour’s first wharf made its appearance in 1896. Regular steamship services to the district had begun in 1867, and these were often diverted to Ōhiwa when the bars at Whakatane or Ōpōtiki became too treacherous.

The lively times at Ōpōtiki township proved temporary. Erosion soon left its mark. By 1915 the town was well and truly doomed, and one by one the buildings vanished. All that remains of that first tiny settlement protrudes from the sand: the stumps of a line of telegraph poles.

In the early 1960s, the new owner of the spit, the Lands and Survey Department, suffering a bout of amnesia, decided the sand was sufficiently stable to offer sections for sale. New Zealanders with beach-front retirement plans leapt at the chance to purchase land. But quicker than sand through an hourglass, their vision of seaside happiness disappeared down the beach with the waves.

For the first few years the erosion was only gradual-6-10 m a year. Then, in 1978, the sea carved 56 m from the foreshore. All the residents could do was stand and stare as their homes were swallowed by the surf. Their earlier attempts to curtail the erosion had taken the form of strewing the foreshore with car wrecks, stacking bundles of manuka and erecting a line of railway irons with strings of tyres attached. That particular eyesore was later buried by the unpredictable sand.