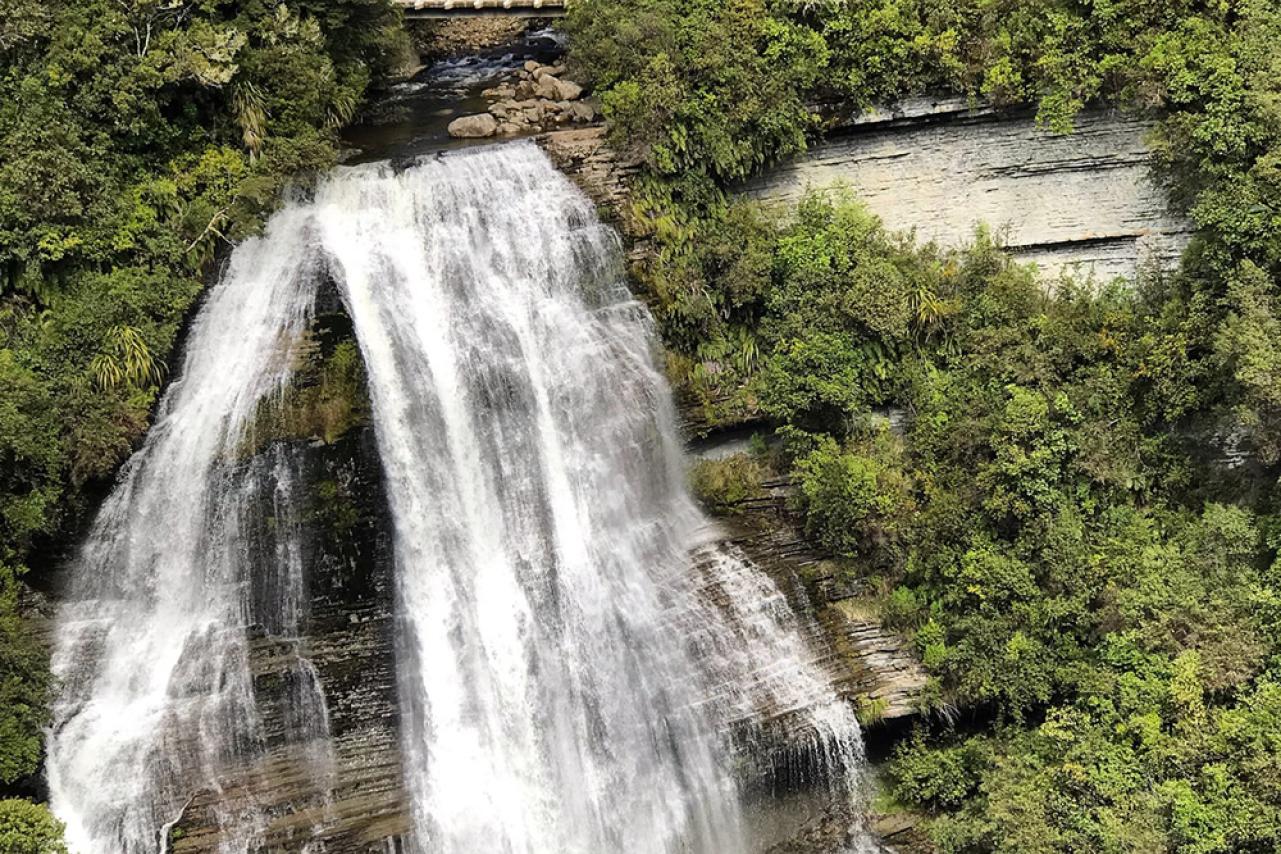

Caption: Te Urewera, one of the most remote rainforest regions of New Zealand. Image by Jacqui Gibson.

Te Urewera: how to experience the natural world in a new way

Te Urewera has long been shrouded in mystery: a mountain region of emerald forests, clear rivers and blue-green lakes populated by Tūhoe, the fiercely independent yet enigmatic iwi known as Nā Tamariki o Te Kohu, the Children of the Mist.

The region is generously endowed with enough jaw-dropping scenery to warrant its own Great Walk at Lake Waikaremoana, and with more culture and history to enthral any heritage-conscious traveller.

Fitting snugly between the Bay of Plenty and Hawke’s Bay, Te Urewera – the first natural landmark to be recognised in New Zealand law as a legal entity in its own right – is signposted by the villages of Tāneatua to the north, Murupara and Ruatāhuna to the west and Wairoa to the east.

Caption: Tūhoe leaders Tamati Kruger (iwi chair) and Kirsti Luke (iwi authority chief executive), Tāneatua. Waterfalls of Te Urewera. Images by Jacqui Gibson.

“We’re asking people to completely rethink their experience of Te Urewera when they come here,” says Tūhoe leader Tamati Kruger.

“Instead of seeing nature as a set of discrete resources to be managed and used, we’re asking people to see Te Urewera as Tūhoe does – as a living system that people depend on for survival, culture, recreation and inspiration. It’s about relating to Te Urewera as its own identity in a physical, environmental, cultural and spiritual sense.”

It’s 8.30am on a Monday morning when I arrive in Tāneatua for a walking tour of the tribal headquarters of Tūhoe with Tamati and fellow Tūhoe leader Kirsti Luke.

An iwi of 40,000 people, Tūhoe has a governance board led by Tamati as Chair, a tribal authority led by Kirsti as Chief Executive, and a 110-person staff responsible for the care of Te Urewera and providing health, education and social services to iwi members.

Tamati, Kirsti and I start our kōrero over a cup of tea and reflect on the law that brought an end to Crown ownership of Te Urewera National Park in 2014.

The world-first law recognised the 212,673-hectare area as a legal entity and the people of Tūhoe as its legal guardian.

“The settlement heralded huge change for both iwi and visitors,” explains Tamati. “It ended several decades of the DOC system – a system people are very familiar with – for an approach that’s based on tribal practices such as kaitiakitanga and manaakitanga.”

As we finish up and head outside, I ask Tamati and Kirsti what visitors to Te Urewera should make of this new era.

“People need to know they’re welcome here,” says Tamati.

“My advice to manuhiri is to come as you are. Be yourself. Bring your friends and your children. Enjoy this wonderful place – its rivers, its trees and its birds. Revel in its mystery. Meet our people. But also take time to hear their stories and learn our history. Be open to experiencing this place in a new way.”

“Revel in its mystery. Meet our people. But also take time to hear their stories and learn our history. Be open to experiencing this place in a new way.”

It’s 11am when I reach Whakatau Rainforest Retreat in the village of Ngaputahi.

Driving on the only road in to one of New Zealand’s most isolated rainforests, I watch paddocks and rundown farm houses give way to dense tawa and rimu forest and scraps of milky-white mist start to appear in the bush canopy like wisps of flyaway candy floss.

Tūhoe guide and eco-lodge owner Hinewai McManus greets me at the roadside wearing a camouflage tracksuit, embroidered leather cowboy boots and a pair of blue mirrored aviators.

She’s lived in Te Urewera off and on for most her life and has an in-depth knowledge of the ngāhere thanks to a childhood of hiking and hunting with whānau.

Today, from a well-forested site on whānau land, she offers tourists a chance to immerse themselves in nature by staying in bush whare and joining her on guided walks throughout the rohe.

Typically, she welcomes visitors with a mihi whakatau – a traditional settling-in ceremony that introduces people to Te Urewera through karakia and waiata.

“From a Tūhoe perspective, it’s the land, the people and our culture that define our concept of heritage,” Patrick McGarvey, Māori Heritage Council member for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, tells me.

“For us, a hillside or an ancient waiata has as much meaning and history as a building belonging to another era.”

During my overnight stay, Hinewai shares stories of Hine-pūkohu-rangi, the mist maiden who lured Te Maunga to Earth from heaven and with whom she coupled to create the people of Tūhoe.

I take part in a tree-planting experience, called Tāne Mahuta – God of the Forest, designed to teach guests how to care for the forest and drawing on mātauranga Māori.

On a half-day bush walk in Whirinaki Te Pua-a-Tāne Conservation Park, Hinewai and I discuss the government deal in 2014 that settled the Crown’s historical wrongs against Tūhoe and recognised Te Urewera as having its own legal identity.

“Did the settlement change much for me, personally?” Hinewai asks in reply to my question during lunch by the river. “Not especially. I’ve spent so much of my life here in the bush. I’ve always seen myself as one of the many kaitiaki of Te Urewera.

“But I’m proud we were the first in the world to introduce such legislation. I’m pleased people from all over the world are coming here to see what being kaitiaki means in practice.”

Talking to Brenda Tahi in Ruatāhuna the following day, she says welcoming tourists to Te Urewera has long been part of Tūhoe culture.

A former government manager and company strategist and now head of a trust responsible for a range of tourism, economic and social ventures in Te Urewera, Brenda also runs Manawa Honey Tours.

Tours take visitors to see Manawa beehives on foot or horseback and sample delicious wild bush honey straight from the hive.

“Many people don’t realise tourism in Te Urewera dates back to the 1800s. In Ruatāhuna, we have some really well-established tourism providers, like Richard and Meriann White at Ahurei Adventures, who offer hiking, horse-riding and marae stays.

Caption: Meriann White of Ahurei Adventures. Maungapohatu, Te Urewera. Images by Jacqui Gibson.

“We’re also seeing amazing social enterprises pop up, like The Blackhouse, a small-scale restaurant run by the Mitai whānau from their home.”

During dinner at The Blackhouse, I learn that all the food on my plate has been locally sourced – either grown by tamariki in school gardens or, in the case of the wild Te Urewera venison, caught by local hunters. Most of the proceeds go into social activities, such as free music lessons for tamariki.

“As Tūhoe, our challenge is to manage tourism in a way that aligns with our aspirations and our culture of looking after this beautiful natural environment for future generations.

“When people come here to spend time with us, they’re buying in to that vision. They’re getting behind our communities and supporting our kaupapa.”

I spend my last day in Te Urewera at the historic marae of Maungapōhatu with Tūhoe kaumātua Richard Tūmarae and his whānau.

On a morning bush walk he tells me: “So many of our young people live outside Te Urewera in cities and overseas. When I can, I like to bring groups – school kids, older people, sometimes tourists – here to walk the land and understand its history.”

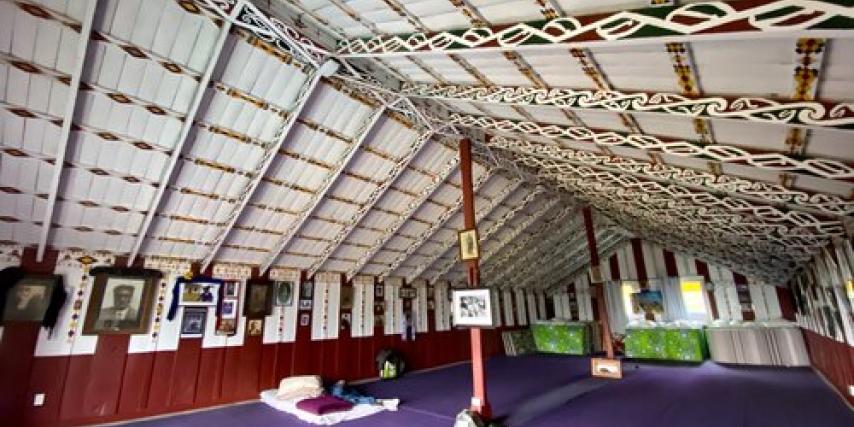

Caption (left to right): Maungapohatu kaumatua and guide Richard Tumarae, wharenui interior, Maungapohatu carving and Maungapohatu guide Atamira Tumarae-Nuku. Images by Jacqui Gibson.

In 2019, Maungapōhatu marae was the site of a formal government pardon. The pardon acknowledged the hurt and shame suffered by the people of Maungapōhatu more than 100 years earlier when their ancestor, Tūhoe prophet Rua Kēnana, was illegally arrested and Maungapōhatu was raided by 70 police officers.

Walking between the wharenui and the kitchen, I see stones commemorating two men, Te Māipi Te Whiu and Toko, the son of Rua, shot dead during the 1916 police raids.

A banquet dinner of crayfish, oysters, chicken, vegetables, salads and Māori fried bread served inside the wharenui by candlelight – considered a no-no in Māori culture – spoke of the unconventional take on tīkanga by Rua, and his special place in the history of Tūhoe as an independent thinker.

The next morning Richard shows me the remnants of the wooden cottage Rua shared with 12 wives. Standing on the hillside, we imagine a time when the tennis courts, now overgrown, were in full swing, and we’re amazed at the lengths the community went to to haul a concert piano into this isolated mountain settlement.

“They came here because they wanted independence and the freedom to express their culture. This story is part of my heritage now and it’s what I’m reminded of each time I come here,” Richard tells me as we turn back down the hill and head for home.

Take a self guided tour of Te Kura Whare

Te Kura Whare is the tribal headquarters of Tūhoe, located at 12 Tūhoe Street in Tāneatua.

Completed in 2014, Te Kura Whare is an award-winning, sustainably designed building based on international principles of non-toxic, environmentally friendly ‘living buildings’.

Built from materials such as dead and fallen trees within Te Urewera and mud from local rivers, Te Kura Whare generates renewable energy, and collects and treats its own drinking water and greywater.

Today it is one of a growing network of living buildings within Te Urewera, which includes Te Kura Tanata in Ruatāhuna and the striking black tribal office set among wetlands at Lake Waikaremoana.

To get to Te Kura Whare, take a 15-minute drive inland from Whakatāne, then park in the main visitors’ carpark. Head in to the main reception area to start your self-guided walking tour of the building.

This story was first published in Heritage New Zealand magazine.